Advanced Search

Casey Gruber, DVM

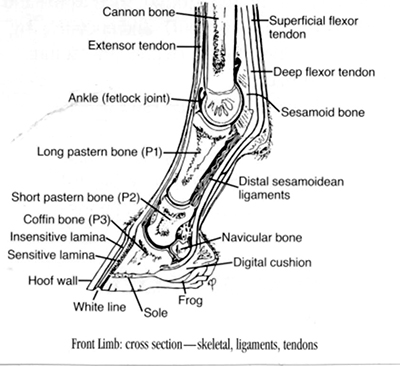

Lameness arising in the front feet accounts for the most soundness issues in horses. However, it has been and continues to be difficult for veterinarians to diagnose a specific injury or source of pain within the foot because the structures can be tough to capture with imaging equipment. Over time, as medical knowledge has expanded, MRI has been incorporated into equine practice, and radiography has improved, we’ve learned a lot about the hoof capsule’s complex anatomy and physiology. The more we understand, the more injuries we can identify. This knowledge has opened doors to many treatment options in the veterinarian’s toolbox. With an accurate diagnosis, the veterinarian can formulate a proper treatment plan and provide an accurate forecast on the horse’s prognosis.

specific injury or source of pain within the foot because the structures can be tough to capture with imaging equipment. Over time, as medical knowledge has expanded, MRI has been incorporated into equine practice, and radiography has improved, we’ve learned a lot about the hoof capsule’s complex anatomy and physiology. The more we understand, the more injuries we can identify. This knowledge has opened doors to many treatment options in the veterinarian’s toolbox. With an accurate diagnosis, the veterinarian can formulate a proper treatment plan and provide an accurate forecast on the horse’s prognosis.

High-Tech Diagnostics

Magnetic resonance imaging has been labeled the “gold standard” for veterinarians to image the horse’s foot. It can provide detailed information about soft tissue, bone, and fluid within the hoof capsule. It can also help veterinarians identify abnormalities they may not otherwise recognize using other diagnostics. Evaluating the horse’s foot using MRI is noninvasive, safe, and can be done with good accuracy either in a standing sedated horse or a horse lying down under general anesthesia. Though MRI is a great option, it does pose some limitations. It’s expensive, and in some parts of the country MRI unit availability is limited. Additionally, MRI imaging requires interpretation by a trained professional and often reveals more than one abnormality. For this reason, veterinarians often look for other clues to help pinpoint a horse’s problem before pursuing an MRI exam or, later, to help determine the significance of the MRI findings.

In spite of these advances in imaging and understanding of the horse’s foot, however, veterinarians still sometimes struggle to arrive at a definitive diagnosis when working up front foot lamenesses. Is advanced diagnostic imaging necessary in every case? Often, the horse and lameness exam alone can yield a wealth of information about a front foot lameness.

History and Signalment

Knowing the horse’s age, breed, and use, as well as the duration of lameness and how quickly it came on, can help the veterinarian formulate a list of possible correlating problems. For example, a 6-year-old Warmblood show jumper coming up lame following a recent class might be dealing with a soft-tissue injury. Alternatively, a 17-year-old Quarter Horse used for team roping with intermittent forelimb lameness over several months might be dealing with a joint or bone-related injury.

Lameness Exam Findings

A veterinarian can learn much and narrow down possible problems simply by completing a thorough clinical exam. Clues that can help include:

-

How the horse moves and travels on different surfaces (packed dirt vs. loose sand);

-

How the foot lands and takes off from the ground during travel;

-

The lead on which the lameness is most pronounced;

-

Response to hoof testers; and

-

Response to flexion tests.

Additionally, veterinarians can learn a lot by evaluating hoof capsule confirmation and health. Distortions in growth, weakness of the hoof walls, contraction of the heels, and uneven wear of the wall or shoe can result from pain or injury in different parts of the foot, how the horse compensates, and predisposing factors to specific injuries. Finally, veterinarians might be able to determine the cause of lameness with specific diagnostic nerve blocks. Using a local anesthetic medication such as lidocaine, the veterinarian can desensitize different parts of the foot, depending on where he or she administers the medication, to detect the location of pain within the hoof capsule. For example, the commonly used palmer digital nerve block generally desensitizes the entire foot, whereas a navicular bursa block generally targets that structure – which cushions the bone from the deep digital flexor tendon – alone. Following a nerve block, the veterinarian assesses the horse to see if he travels differently.

Based on these exam findings, the veterinarian can then use digital radiography to assess suspected bony problems.

In summary, front foot lameness is common in horses and continues to frustrate owners and challenge veterinarians. Fortunately, owner-provided information and a thorough lameness examination can help practitioners start meaningful investigations. MRI has improved our understanding of the horse’s foot and serves as a valuable tool but is not an absolute necessity.

Article provided by AAEP Media Partner, The Horse.